Rainbow Trout

by John Holt

Should there be one species embodying all the characteristics an angler would want in a perfect freshwater sportfish, the rainbow trout would have to be on anyone's short list. Strong, beautiful, acrobatic, requiring skill to take consistently, inhabiting pure waters usually in beautiful settings — basically the rainbow is a designer sportfish perfect for a variety of fishing appetites.

The rainbow is native to North America with a natural range of northern Mexico up into Alaska. You can catch the fish in New York, Ontario, Wisconsin, South Dakota, Wyoming, California — throughout the continent. More rainbows are taken by anglers than any other species of trout, and no other fish is raised and stocked as extensively throughout the world. Rainbows are found in unlikely places such as North Dakota, fee trout ponds outside of Cleveland or at put-and-take lakes in Florida. This is the closest thing there is to a universal trout (or gamefish for that matter).

Rainbows grow to exceptional size. One weighing over 52 pounds was taken from Jewel Lake, British Columbia. The world record by an angler is 42 pounds, 2 ounces from Bell Island in Alaska. The species takes its name from a red lateral band that varies widely in intensity from deep, pink shading toward red during spawning in some rivers to the faintest suggestion of rose in certain lake-dwelling races. The coloring of the gill plates will match the intensity and shading of the lateral band. The rainbow can be anywhere from green, to blue, to olive-brown on its back. The flanks are usually silver and the belly is white. Stream dwellers tend to be heavily marked with black spots.

There are many subspecies, races and hybrids. Races of non-migratory rainbows include Eagle Lake, Arlee, Kamloops, Shasta, Kern River and Royal Silver. Rainbow eggs have been shipped to New Zealand, northern India, South Africa, Europe, Chile, Argentina, Japan and anywhere else anglers wander. The species readily cross-breeds or hybridizes with other salmonids including cutthroat and goldens, which produce a beautiful and feisty fish.

The rainbow resembles a cutthroat in some waters, but the two can be distinguished by the fact that the rainbow has no teeth on the back of its tongue (hyoid). In its anadromous or sea-run form, the rainbow is known as a steelhead and spends a sizable portion of its life in the ocean, or one of the Great Lakes, before returning to its native stream to spawn.

Rainbows Are Spring Spawners

Rainbows are spring spawners. Spawning occurs from February through June for inland populations with those swimming in some cold-water lakes holding off until as late as August in isolated cases. The fish build redds, or nests, in the gravels of rivers and streams near the end of a pool or in inlet or outlet streams when occupying lake environments. If there is not any suitable spawning area in a given water, the females gradually reabsorb their eggs. Females lay roughly 1,000 eggs per pound of body weight. These eggs hatch within two months under normal conditions. Both male and female experience a large decline in weight following spawning — up to one-half the body weight in males. As a result, the fish provide poor sport for several weeks after this activity. At these times, the trout are dull in color, loose of flesh and anemic in behavior. Anglers have caught post-spawn 5-pound rainbows that have turned on their sides and come meekly to net as soon as they felt the bite of the hook — not a very energizing experience.

Rainbows live between seven and 12 years depending on the location. On the average, a 2-year-old rainbow is about 8 or 9 inches, but in certain fertile lakes of the West, the species grows as much as an inch per month for the first two seasons, producing trout of 2 feet, and 7 pounds or more.

Rainbows prefer the fast water sections of rivers and also cold-water lakes, ponds and reservoirs. Along with the rest of the trout family, they also thrive in spring-fed creeks.

There is not a more acrobatic fish in freshwater than a rainbow taken from fast current. In spring, while casting a spoon at lake inlets, you'll often find fish over 5 pounds coming out of nowhere and slamming down on the lure. Before an angler can collect himself, the rainbow has already torn into his line while tailwalking, crashing and leaping out into the lake. Clamping down to check the fish usually equals a break-off. There is no way to handle such a fish with lightweight gear. Big rainbows create heart-stopping experiences.

In lakes, large rainbows spin anglers in float tubes around. Big 'bows fight anglers for 20 minutes or more before fraying the line and snapping free to safety. Pound for pound, river-run rainbows are the strongest of the trout, with browns coming in at a close second.

When fishing rivers and streams, with the intention of catching rainbows, look for moving water. It will usually be the fastest water you can find.

The species loves to feed in fast runs while holding down on shelves just above drop-offs into deep pools. The current may be racing along at the surface, but at the bottom (the benthic zone) surface drag between the streambed and the water reduces the flow to nearly zero. This is an ideal situation for big trout to hold in — little effort is expended, food passing overhead is visible, yet the fish's presence is masked by the rippling currents staggered throughout the water column.

To appreciate the masking aspects of moving water, walk out on a bridge spanning a trout stream, one where there are visible trout holding below you. Pick out one fish and watch as it moves from side to side, and slightly up and down stream while feeding. You will notice that as the trout moves underneath a seam where two differing speeds of water converge, a second or two is needed for your eyes to readjust and pick out the fish again. The same visual screen hampers predators flying overhead or prowling a bank. Cover as slight as this is the difference between a trout's life and death in a river.

Work Riffles On Sunny Days

A good place to prospect for rainbows during the height of a sunny day is in riffles, for the reasons mentioned above and because the water washes down plenty of aquatic insects. Usually these insects occur in nymphal form (nymphs are worm-like in appearance and spend as much as three years crawling along the stream bottom feeding on other insects and plant life before rising through the water to take flight and mate above the water).

Coupled with the rich oxygen content of the water, riffles are prime spots for rainbows. Spinners cast quartering upstream, and retrieved fast enough to create the designed action, often produce rainbows on every cast in good streams. Bait and nymph fly patterns drifted through these normally rocky bottoms also produce. Spoons tend to be rolled over in the current here, more often than not spooking the trout.

Often rainbows hold steadily in water that is a combination run/riffle — deep with slight rippling on the surface. The dark appearance of the water is an indication of depth, and the rippling tells you that the current is swift, maybe as much as 7 miles per hour, moving over an uneven bottom. Once again, this is a perfect habitat with the prerequisites of current-induced cover, available food and plenty of oxygen. Of the major species of trout, only the cutthroat displays a similar preference for this type of water, but not to the extent the rainbow does.

To some degree, all trout are herbacious, meaning that a portion of their diet consists of plants (mainly algae and other aquatic plants). Rainbows make a greater use of this food source than any other trout (with the cutthroat again being closest in utilizing plants for food). Working any area with aquatic plants is obviously a good idea for this reason, and the fact that weedbeds are nurseries for aquatic insects such as caddis flies, mayflies and stone flies along with freshwater shrimp, known as scuds, also helps.

Working a nymph down through these channels nearly always turns up a good fish, but a sturdy leader is required to avoid breaking-off in the weeds. Bait such as worms drifted through these spots are just as effective. Spinners also work well, but require a fine touch and make for difficult, often frustrating fishing.

Because rainbows will take to the air, frequently jumping a couple of feet out of the water, maintaining tension on the line is difficult but necessary. If the fish gains too much slack, it can throw the hook or crash back down on the line, using its body weight to snap the slender connection. There is not much an angler can do when a large rainbow accelerates across the surface of the water except to reel in slack as fast as possible and raise and lower the rod to maintain a steady, firm pressure on the line and trout. Most rainbows gain their freedom while suspended in air, shaking their heads.

When seeking rainbows, the most important thing to look for is moving water — deep, fast runs, shelves at the heads of pools, riffles, and combination deep runs/riffles. Also, work any aquatic plant growth. Spinners are much better than spoons and wooden minnows in this kind of water. Nymphs and bright streamers work with a fly rod, and worms are the bait of choice.

Steelhead Are Sea-Run Rockets

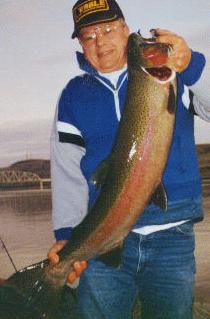

Something wonderful happens to a rainbow trout when it takes leave of its native rivers and runs downstream to spend a few months, or even years, in the big water — whether it be the Pacific Ocean, or one of the Great Lakes. The trout return to the rivers of their birth larger and tremendously stronger than when they left. These silver rockets are known as steelhead.

For hordes of West Coast and Great Lakes anglers, there is only one sportfish worthy of their attention and this is the steelhead. A rainbow is an impressive fish, but a steelhead takes on the strength and power of a salmon, which when combined with the acrobatics associated with the rainbow becomes an awe-inspiring trout to say the least.

Unlike Pacific salmon, steelhead may return to spawn in their home waters more than once; whereas the salmon die shortly after spawning. There are two distinct races of steelhead — winter-run and summer-run. Steelhead are silver when they first enter the rivers, but gradually as they move upstream and near their spawning grounds they begin to darken and the red band appears. Sexual changes in their physiology are responsible for this transformation which also includes the development of a kype in males. They then resemble rainbows except that they are slimmer in body shape. The fish grow large, though the average range on the coast is somewhere between 6 and 15 pounds. In the rushing, isolated rivers of British Columbia, steelhead reach weights of around 40 pounds.

It is believed that these fish evolved from the rainbow after periods of geologic upheaval, such as the ice age and volcanic eruptions. They adapted to take advantage of new spawning and feeding habitat provided in the ocean. Whether or not steelhead feed while in freshwater is the source of much unresolved debate. They do lose a good portion of body weight at this time, but they also will hit sacks of eggs and patterns that imitate these eggs. No one really knows for sure at this time. They may also strike out of an instinct, that has reached a fever pitch during spawning, to defend territory.

Summer And Winter Races

Steelhead that enter the rivers in spring, summer and fall are known as summer-run. Those entering in late fall, winter and early spring are known as winter-run. On most rivers these two races, or strains, will spawn at approximately the same time, late winter and early spring. Steelhead that enter freshwater as immature fish but then mature in the following six months to a year are also known as "green" fish, while the winter runs are mature or "ripe." Strains imprinted with these characteristics, and planted in the Great Lakes, exhibit quite similar behavior.

The two strains of steelhead are distinct races that maintain racial integrity when it comes to selecting periods of freshwater residency and spawning. While the two races may enter a given river at the same time, there is no evidence that the races mix. The largest steelhead tend to appear in rivers at the end of a given run and winter-run fish are generally the biggest, though summer-run fish may reach 20 pounds.

Steelhead that have completed spawning and are returning downriver to the sea are known as kelts, a name for Atlantic salmon in a similar stage of their lives. The fish have lost much of their bright spawning color and will not regain a "healthy-looking" appearance until they have had the opportunity to feed in the ocean. Despite their appearances, both sexes are in relatively fine physical condition following spawning. Fishermen usually run into these fish in March and April, and many streams are closed at this time to protect the fish.

The main difference between fishing for steelhead on the Pacific Coast and along the Great Lakes is the size of the tributary. Coastal rivers like the Columbia are huge, over three miles across in some spots, while those in the Midwest are much smaller. As an example, those in Door County in Wisconsin have good runs of fish approaching 20 pounds that provide excellent sport in streams sometimes no more than 25 feet wide and just a couple feet deep.

Steelheading Is Tough At Times

Steelhead fishing is one discipline (an appropriate term when you consider that it often takes hundreds, maybe thousands, of casts in wet, freezing weather before connecting with a fish) where knowing the precise location of the run in a river is not merely a convenience, it is an absolute necessity. The trout do not live year-round in the river. You cannot take the fish by merely working good-looking holding areas like you do for inland trout. Often, the steelhead are already upstream or still downriver staging before a big push upstream. Any method that will take rainbow trout will work with steelhead, though the tackle used will be larger because of the nature of the rivers the fish return to.

Heavy spinning gear is needed to cast large spoons and wobbling plugs. A 7.5-foot spinning rod with 10-pound test line or an 8-foot baitcasting setup with 12-pound test are ideal. These will handle 3/8- to 3/4-ounce lures. Spoons are often cast upstream, into the deep races of a river, and retrieved while they run along the bottom and then finally swing in the current. Wobbling plugs work best when they are allowed on the retrieve to slowly drift in the current which produces a fluttering action. Fluorescent colors seem to work better than regular ones for this fishing. Drift spinners are a West Coast favorite. They are available in bright colors. These lures have propeller-like rubber wings that spin the lure on a wire shaft and are used by both trollers and drift fishers in larger rivers.

As with any trout fishing, spinners produce with steelhead, but they must be in large sizes and include fluorescent colors — both weighted and unweighted. Another good choice is a marabou jig, both because it easily sinks to the depth of the fish and does not often snag.

Spoons of from an inch to 3 inches, in plain and hammered brass, or silver, along with those with streaks of red or white or a red-and-white finish also work well.

Spawn And Yarn Works Well

Many natural baits are used for steelhead, and they include shrimp, single eggs, night crawlers and salmon or steelhead spawn mixed with yarn. When using the spawn-yarn method, baitholder hooks with barbs on the shanks that prevent the snell from reaching the hook eye work best. The loop of leader that lies between the hook eye and snell is slipped over the bait to hold it in place. The yarn, which acts as a simple but effective fly, is tied directly on the leader above the hook. This is done by laying a 3-inch piece of fluorescent tying yarn on a flat surface and crossing it with the leader. Over the leader and opposite the tying yarn, lay three, inch-and-a-half strands of yarn. Gather the tying yarn ends and tie a square knot, sliding this to the hook eye and trimming the strands so they are even.

When drift fishing, you must experiment with the amount of weight until the fly, bait or lure is just barely bouncing along the bottom, most often with a 3/16-inch-diameter pencil lead attached by running the line through a small hole drilled in the head of the weight. This line should be lighter in weight than the casting line so if snagged only the lead breaks off saving an expensive lure. The easiest method to adjust this weight is to attach six inch sections which can be cut to the desired weight to match given stream conditions. Surgical tubing slipped over the ring of a three-way swivel and cinched above the ring with nylon thread keeps the setup from twisting around the main line and itself. Just slip the lead into the tubing.

For the fly fisher, at least a 9-foot rod that can handle a minimum of a 7-weight line is required. Better still is a 9 and 1/2-footer for 8 and 9-weight lines, preferably shooting heads that allow the angler to add distance necessary to reach holding areas on larger rivers.

A good example of a hand-tied steelhead leader, for fly fishing would be one with 40 inches of 25-pound test, 34 of 20, 8 of 15, 8 of 12 and 18 of 10. Another slightly lighter leader would consist of 38 inches of 25-pound test, 32 of 20, six each of 15, 12 and 10, and 20 inches of 8-pound test.

There are many patterns for steelhead. Some of the more popular ones include the Orange Shrimp, Umpqua, Skykomish Yellow, Stilliguamish Sunrise, Royal Coachman, Skunk, Kalama Special and Admiral.

Whatever method is chosen to be used for these fish, it only takes the feel and sight of one steelhead as it rockets across the water and then powers straight up a mighty rapid, to hook the angler for life.